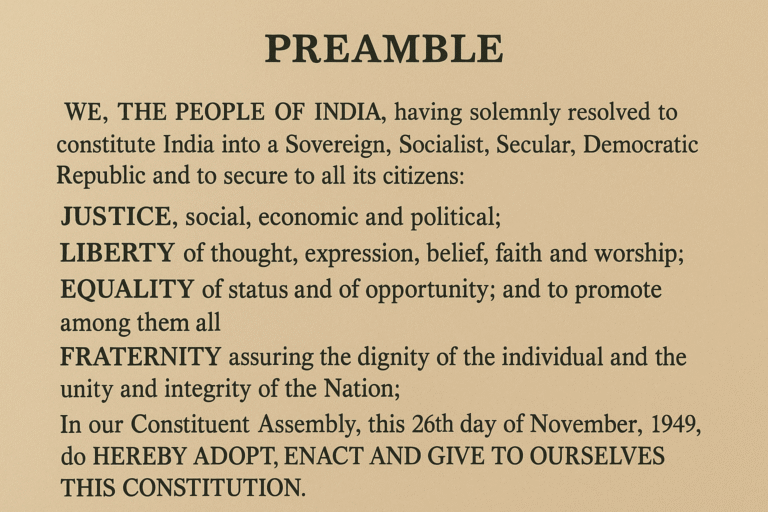

📜 Historical Underpinnings of the Indian Constitution

Company Rule

1600 – East India Company Formed

- On 31st December 1600, Queen Elizabeth I granted a Royal Charter to the East India Company.

- The charter gave exclusive trading rights to the Company in the East Indies for 15 years.

- It began as a purely commercial venture, not a political one.

- This was politically backed by the British Crown – the Company was a private enterprise, but with state support.

- But this monopoly meant no other British merchants could legally trade in the region, giving it a legal status backed by the British Crown.

🧠 Key Term: Chartered monopoly → First sign of foreign economic intrusion in India.

1608 – First English Factory in Surat

- British established their first factory at Surat with the permission of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir.

- This marked the formal entry of the British in India’s economy.

💡 Note: Other European powers also had factories (Portuguese, Dutch, French), but British later dominated.

1707 – Death of Aurangzeb → Mughal Decline

- After Aurangzeb’s death, centralized Mughal authority collapsed.

- Power was now fragmented among:

- Regional rulers (Marathas, Nizams, Nawabs)

- Foreign invaders (Afghans, Persians)

- European traders

🧠 Key Outcome: Political vacuum → East India Company found an opportunity to expand from trade to territory.

1739 – Battle of Karnal

- Nadir Shah of Persia defeated Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah Rangila.

- Delhi was looted, including the Peacock Throne and Kohinoor diamond.

- The Mughal Empire’s symbolic prestige was destroyed.

📌 Result: British realized Indians would not unite under Mughal leadership → easier to manipulate regional rulers.

1757 – Battle of Plassey: Beginning of British Political Rule

- British vs Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah of Bengal.

- British bribed Mir Jafar (commander-in-chief) → betrayed Nawab during war.

- British victory → installed Mir Jafar as puppet Nawab.

📌 Outcome:

- British gained de facto control of Bengal.

- Began extorting money from puppet rulers — “Company Bahadur turned from trader to kingmaker.”

🧠 This is considered the beginning of British political dominance in India.

1764 – Battle of Buxar: Legal Legitimacy

- Combined Indian forces (Shah Alam II, Nawab of Bengal, Nawab of Awadh) lost to the British.

- British emerged as military superpower in Northern India.

- 1765 Treaty of Allahabad:

- Mughal Emperor gave Diwani rights (revenue collection) of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa to the Company.

📌 This gave the British the official right to tax Indian people.

1765–1772 – The “Dual Government” in Bengal

- Invented by Robert Clive.

- Nawab retained administrative duties, while the Company took revenue collection.

- British had power without responsibility.

- Nawab had responsibility without power.

📌 Consequences:

- Massive corruption, famine, and misgovernance.

- Bengal Famine (1770) killed 10 million people (1/3 of population).

🧠 Dual government proved the Company could not govern. It was exploitative and unaccountable.

Quid Pro Quo & Corruption (1760s–1770s)

💰 “Loot of Bengal” and Bribery in Britain

- Company officials (like Robert Clive) became rich overnight (called Nabobs).

- Bribed British MPs to protect the Company’s rights in Parliament.

- Many returned to Britain with fortunes of £300,000–£500,000 (₹300–500 crore today).

- In return, they helped fund political campaigns, bought Parliament seats.

🧠 Corrupt officials in India + protected by corrupt MPs in Britain → unaccountable Company rule.

1772 – East India Company Nearly BANKRUPT

- Despite looting India, Company’s mismanagement led to bankruptcy.

- It asked the British government for help.

- Parliament bailed it out with £1.4 million (over ₹1400 crore today).

- Public in Britain was OUTRAGED: “Why save a corrupt company looting India?”

🧠 Still, this Act marked the first step from Company rule to Crown oversight — the beginning of constitutional control over India.

📜 CHARTER ACTS (1773–1853)

1. Charter Act of 1773

🔸 Also known as the Regulating Act

📌 Purpose: To control corruption and mismanagement in East India Company rule.

Key Features:

- Designated Governor of Bengal → Governor-General of Bengal (Warren Hastings).

- Created Executive Council of 4 members (no vote for Governor-General).

- Established Supreme Court at Calcutta (1774).

- Prohibited private trade and bribes by Company servants.

- First time British Parliament intervened in Indian affairs.

🧠 Marks the beginning of British constitutional control in India.

🏛️ Amending Act of 1781 (Act of Settlement, 1781)

(A vital correction to the Regulating Act of 1773 – The foundation of Judicial-Executive relations in India)

🔹 Background Context

Before 1781, the British had introduced the Regulating Act of 1773, which:

- Established the Governor-General of Bengal (Warren Hastings as the first).

- Created the Supreme Court at Calcutta in 1774.

- Aimed to bring East India Company under British Parliamentary control.

But the Act of 1773 had serious flaws:

- Jurisdictional overlap between Supreme Court and Governor-General-in-Council.

- Confusion over who could be tried by the Court (British citizens only or Indians too?).

- Frequent clashes between Executive (Company officials) and Judiciary.

This led to chaos and institutional rivalry.

🟨 Why Was the Amending Act of 1781 Passed?

📌 To correct the flaws in the Regulating Act of 1773.

Key Purpose:

“To define the relationship between the Supreme Court and the Governor-General-in-Council.”

🔍 Main Problems It Addressed:

- Misunderstanding of Supreme Court’s jurisdiction

- Conflict between Judiciary (Supreme Court) and Executive (Governor-General’s Council)

- Lack of clarity on the Court’s territorial and personal jurisdiction

📜 Relevance to Indian Constitution

- Directly relates to Article 50 of the Constitution: “The State shall take steps to separate the judiciary from the executive in the public services of the State.”

💡 This Act marks the first colonial step towards the doctrine of Separation of Powers in India.

📜 Pitt’s India Act, 1784

(A turning point in British control over Indian administration)

🔹 Background

After the Regulating Act of 1773 and its flaws, followed by the Amending Act of 1781, it was clear that the British needed a stronger mechanism to control the East India Company’s political affairs.

Hence, came the Pitt’s India Act, 1784, named after British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger.

🎯 Key Objectives of the Act

- To reduce the Company’s political autonomy.

- To establish a clear distinction between commercial and political functions.

- To bring Indian administration directly under British government supervision.

📝 Mains Answer Enhancement

“The Pitt’s India Act of 1784 laid the constitutional foundation for a centralised colonial state. While it retained the East India Company in name, it reduced it to an economic instrument of the British Crown, marking the real beginning of direct British control over Indian governance.”

2. Charter Act of 1793

📌 Context: Renewal of Company Charter for 20 more years, but reforms needed after Pitt’s India Act 1784.

Key Features:

- Reinforced Pitt’s India Act: Governor-General’s power increased; could override Council decisions.

- Company’s trade monopoly continued for next 20 years.

- Governor-General of Bengal authorized to override Madras and Bombay governors in all matters.

- Increased salaries for Company officials to discourage corruption.

- Royal approval required for Company appointments (beginning of Crown influence in civil services).

🧠 Power of Governor-General centralised further. No major structural change, but British control tightened.

3. Charter Act of 1813

📌 Context: Heavy criticism in Britain for Company’s monopoly; rise of British private merchants wanting access to India.

Key Features:

- Ended the Company’s trade monopoly in India — except for trade with China and tea trade.

- Company’s political and administrative functions continued.

- Allowed Christian missionaries to enter India (education, conversions).

- Company asked to spend ₹1 lakh/year on education.

🧠 First time British state began shaping Indian society through education and religion.

4. Charter Act of 1833 – Most Important & Radical

📌 Context: Industrial Revolution in Britain, need for free trade, and administrative centralisation.

Key Features:

🏛️ 1. Governor-General of India created

- William Bentinck became the first Governor-General of India (not just Bengal).

- Centralised administration — Bombay and Madras were now fully subordinate.

⚖️ 2. Legislative Centralization

- Ended legislative powers of Bombay & Madras.

- A law-making council for all of India was created.

💼 3. End of Company’s Trade Monopoly

- All trade ended — Company became only an administrative body.

- Complete commercial disassociation.

🏫 4. Law Commission introduced

- Lord Macaulay appointed to codify laws.

- Led to Indian Penal Code (drafted 1837, enacted 1860).

⚖️ 5. Equality Clause (first attempt)

- Said Indians should be eligible for all offices under Company (not implemented).

🧠 Turning point: Company became a purely administrative agency. Seeds of Indian civil rights and codified law sown.

5. Charter Act of 1853 – Last Charter Act

📌 Context: Growing demand for Indian representation, more governance issues, and criticism of Company rule.

Key Features:

🧑⚖️ 1. Legislative–Executive Separation

- Council of Governor-General split into:

- Executive Council (admin duties)

- Legislative Council (law-making)

- 6 new members added to Legislative Council (including Indians in future).

👨💼 2. Open Competition for Civil Services

- Introduced merit-based civil service exams (for all, including Indians).

- First major step toward Indian Civil Services (ICS).

🕰️ 3. No Fixed Charter Duration

- Unlike earlier Acts, this did not renew the Company charter for a fixed period.

- British Parliament kept the right to terminate Company rule at any time.

🧠 Marks the beginning of the end for East India Company’s rule.

Crown Rule

1. Government of India Act, 1858 – End of Company Rule

📌 Context:

- After the 1857 Revolt (First War of Independence), the British realized the Company was unfit to rule.

- People blamed Company misrule, disrespect for Indian traditions, and lack of accountability.

🏛️ Key Features:

- Company rule abolished; India directly under British Crown.

- Title of Governor-General of India changed to Viceroy of India (first: Lord Canning).

- Established a new office: Secretary of State for India in the British Cabinet.

- Had complete control over Indian administration.

- Advised by a 15-member Council of India.

- All civil and military powers transferred to the British Parliament.

🧠 Significance:

- India became a formal British colony.

- Laid the groundwork for centralized and bureaucratic governance.

- Marked the beginning of Imperial Legislative Reforms.

2. Indian Councils Act, 1861 – Beginning of Representation

📌 Why Needed?

- British needed Indian support post-1857.

- They wanted to reassure Indian princes and elites.

🗳️ Key Features:

- Legislative Councils reintroduced at Central & Provincial levels.

- Indians were nominated (not elected) to Legislative Councils.

- First time Indians entered British legislative bodies (Raja of Benaras, Maharaja of Patiala).

- Decentralization:

- Powers of Bombay & Madras restored.

- Governor-General could issue ordinances during emergencies (for 6 months).

🧠 Significance:

- Beginning of Indian legislative participation, though symbolic.

- Laid foundation for future bicameralism and provincial autonomy.

3. Indian Councils Act, 1892 – Indirect Elections Begin

📌 Background: Rise of Indian National Congress (est. 1885) demanding more representation.

🗳️ Key Features:

- Introduced indirect elections (not by people, but by local bodies and institutions).

- Expanded number of members in Central & Provincial Councils.

- Gave members the right to ask questions, but not vote.

🧠 Significance:

- First step toward representative governance.

- Recognized Indian political aspirations — start of constitutional agitation.

4. Indian Councils Act, 1909 (Morley–Minto Reforms)

📌 Context:

- Partition of Bengal (1905) → Uproar

- Rise of Extremist Congress + Muslim League (1906)

🗳️ Key Features:

- Introduced separate electorates for Muslims → seeds of communalism.

- First time Indians were appointed to the Viceroy’s Executive Council (Satyendra Prasad Sinha).

- Enlarged Central and Provincial Councils.

- Members could discuss budgets and ask questions.

🧠 Significance:

- First constitutional recognition of communal identities.

- Enhanced Indian participation but divided politics along religious lines.

💡 Concept: “Good Governance” in British Rule

Though not sincere, the British marketed reforms as efforts to improve administration and governance:

- Civil services, rule of law, codification of laws, judicial independence (in structure).

- Introduction of education, railways, postal system, municipal reforms.

- These were aimed more at imperial control, but provided a framework India later built upon.

🧠 Modern administrative values like civil service exams, all-India services, neutrality — have roots in this era.

📌 What is a Colony?

“Colony means — no legal rights, no political rights, and a foreigner as the head of state.”

How Federation Would Be Achieved in India (Pre-Independence Vision)

1️⃣ British Indian Provinces – demand Provincial Autonomy

🧾 Condition: Internal constitutional restructuring

- Demanded division of power between Centre and Provinces

- Demanded bicameralism and autonomous provincial legislatures

- Wanted responsible governance (not controlled by the Viceroy)

✅ Met partially under:

- GOI Act 1919 → Dyarchy

- GOI Act 1935 → Provincial Autonomy

2️⃣ Princely States – give up suzerainty

👑 Condition: External political shift

- Had internal sovereignty, but under British suzerainty

- To join federation, they had to give up suzerainty voluntarily

- They would retain internal matters but become part of the federal structure

❌ Never fulfilled:

- Princely states refused to join → federation failed

🤔 Why the Federation Never Happened?

- Princely states refused to join — they didn’t want to lose their privileges.

- Indian National Congress also rejected it, as they wanted full Swaraj (self-rule), not British-led federalism.

- Thus, though the Act created the blueprint, the federation never materialized.

✅ Dominion ?

Dominion means — a country has legal and political rights, but the head of the state is still a foreigner.

🇮🇳 Indian Context:

- Demanded in 1929: Congress shifted from Dominion to Purna Swaraj at the Lahore Session.

- Still, Cripps Mission (1942) offered Dominion Status (rejected by Congress).

- Indian Independence Act 1947 granted Dominion Status to both:

- India → till 1950 (Republic day)

- Pakistan → till 1956

✅ India became a fully Sovereign Republic on 26th January 1950.

5. Government of India Act, 1919 (Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms)

📌 Background:

- WWI: Indians supported British war efforts, expected reforms.

- 1917: Montagu Declaration – “Gradual development of self-governing institutions in India.”

Key Features:

1. Diarchy at Provincial Level

- Powers divided into:

- Reserved subjects (law/order, police, revenue) – by British officials.

- Transferred subjects (education, health, agriculture) – by Indian ministers.

- Governor could override Indian ministers anytime.

Diarchy in 1919 – Why It Was a Sham Reform?

What Was Diarchy?

Diarchy means dual rule — introduced at the Provincial level under the Government of India Act, 1919.

Two categories of subjects were created:

- Reserved Subjects – Controlled by British-appointed Executive Councillors (e.g., law & order, police, land revenue, irrigation).

- Transferred Subjects – Handled by Indian ministers (e.g., education, public health, agriculture, local self-government).

❌ Why It Was a Sham

1. Real Powers Kept with the British

- All critical and high-impact departments were kept under Reserved subjects.

- Indian ministers had no control over:

- Police

- Revenue

- Judiciary

- These areas defined real governance — so Indian ministers were powerless showpieces.

2. No Autonomy for Indian Ministers

- Even in Transferred Subjects, British Governor could override decisions.

- Ministers had to answer to the Governor, not to the elected legislature.

📌 Ministers were called “helpless secretaries” — not policymakers.

3. Governor Was Supreme

- Had emergency powers, discretionary powers, and veto.

- Could dissolve legislative council, ignore advice of ministers, and issue ordinances.

🧠 Real power remained centralised in the hands of the British.

4. No Real Accountability

- Indian ministers were responsible to the legislature, but legislature had:

- No control over finances

- No control over law and order

- The British executive was not responsible to the Indian people.

5. Created Frustration, Not Federalism

- Indian leaders participated (e.g., Congress in early 1920s) but became disillusioned.

- Many resigned, realizing it was just “governance without power”.

- This led to a shift from cooperation to confrontation (e.g., Non-Cooperation Movement 1920).

UPSC Mains-Ready Insight:

“The diarchy introduced by the Government of India Act, 1919 was more of a political illusion than administrative reform. Power remained with the British under the mask of Indian participation. It was a dual government where only one side ruled and the other side obeyed.”

2. Bicameralism introduced at Central level:

- Legislative Assembly (Lower House)

- Council of States (Upper House)

❌ Why Bicameralism in 1919 was a Sham?

1. Lack of Real Power

- The Legislative Assembly (Lower House) and Council of States (Upper House) had no power over the Executive.

- The Viceroy’s Executive Council was not accountable to the legislature.

- Laws could be passed even without legislative approval using special powers.

🔁 There was structure, but no substance.

2. Viceroy’s Overriding Powers

- The Viceroy could override any decision, dissolve the legislature, or refuse assent to any bill.

- He also had ordinance-making powers, bypassing the legislature completely.

🧠 This made the legislature more of a “decorative body” than a sovereign institution.

3. Very Limited Franchise

- Only about 2–3% of the population could vote — mostly landowners, taxpayers, and elites.

- Ordinary Indians had no voice in the law-making process.

📌 This meant it wasn’t a people’s parliament, but a privileged club.

4. Reserved Subjects Out of Reach

- Central subjects like foreign affairs, defense, railways, police were reserved — under direct British control.

- Only minor matters could be discussed by Indian members.

5. No Control Over Budget or Ministers

- Legislature could debate the budget, but had no authority to amend or reject it.

- Ministers were nominated, not elected, and did not answer to the legislature.

UPSC Mains Angle:

“Though the Government of India Act, 1919 introduced bicameralism at the Centre, it was a structural showpiece. With the Viceroy’s veto powers, a restricted electorate, and no legislative control over the executive, it was a parliament in form, not in function.”

3. Franchise expanded (but limited to property/tax payers).

4. Public Service Commission – Mains Perspective

The Government of India Act, 1919 laid the foundation for an impartial and merit-based civil services system in colonial India by providing for the establishment of a Public Service Commission. Though implemented in 1926, it marked a shift from executive-controlled recruitment to an institutional mechanism aimed at professionalizing governance — a legacy that continued into independent India as the UPSC.

🧠 Significance:

- Introduced decentralized legislative structure.

- First serious attempt at power-sharing, though very limited.

- Indian dissatisfaction → Non-Cooperation Movement (1920).

✊ Non-Cooperation Movement (1920) – In Brief

📜 Background:

- Launched in response to:

- Rowlatt Act (1919) – allowed detention without trial

- Jallianwala Bagh Massacre (1919) – brutal repression of peaceful protesters

- Khilafat Movement – Muslim demand to preserve the Caliph

- Failure of 1919 Act – diarchy seen as a sham reform

🧠 Gandhiji’s Strategy:

- Promote non-violent non-cooperation with British rule:

- Boycott of foreign goods, titles, elections, schools, courts

- Promotion of Swadeshi, Khadi, and national education

- Encourage resignation from British institutions

🔥 Impact:

- First mass-based, nationwide movement led by Gandhiji

- Brought Hindus and Muslims together (Khilafat + Swaraj)

- Created political awakening among rural masses

🛑 Ended:

- February 1922, after Chauri Chaura incident (violent mob killed 22 policemen)

- Gandhiji called off the movement to preserve non-violence

🧠 UPSC Insight:

“The Non-Cooperation Movement transformed Indian nationalism into a mass movement. It marked a shift from constitutional agitation to direct action under Gandhian leadership, though its premature end exposed the challenges of controlling mass civil disobedience.”

the Government of India Act, 1919 had a provision that a commission would be sent after 10 years to review its working — that would be 1929.

But the British sent the Simon Commission early in 1927, and this triggered massive nationwide protest.

Let’s break it down.

📜 Simon Commission – 1927 (In Brief, Mains Perspective)

🧭 Why Was It Sent Early?

- 1919 Act said: a review commission will be sent after 10 years (i.e., in 1929).

- But due to political instability in Britain, the Conservative government sent it 2 years early, in 1927, to pre-empt future challenges.

- Main goal: to assess how well diarchy and constitutional reforms were working.

❌ Why Massive Opposition?

❗ All members were British — No Indian representative

Led to the slogan: “Simon Go Back!”

- Seen as insulting and colonial arrogance

- Indian political parties — Congress, Muslim League (Jinnah), Hindu Mahasabha, all boycotted

- Nationwide hartals, black flag demonstrations, and protests

🔥 Impact on Indian Politics:

- Gave rise to nationwide unity against British racism

- Led to Lala Lajpat Rai’s death (after police lathi charge in Lahore)

- Forced the British to invite Indian leaders for Round Table Conferences later

- In response, Congress adopted the Purna Swaraj demand in 1929 (Lahore Session)

🧠 UPSC Mains Insight:

“The Simon Commission exposed the colonial mindset of exclusion and racial superiority. Its rejection united Indian political forces across ideologies and directly paved the way for the Purna Swaraj resolution of 1929.”

Simon Commission, Round Table Conferences, and Civil Disobedience Movement

📘 1. Simon Commission (1927)

- Appointed to review the working of the Government of India Act, 1919.

- All members were British, with no Indian representation.

- Led to nationwide protests with the slogan: “Simon Go Back!”

- Major parties, including Congress, Muslim League, Hindu Mahasabha, boycotted it.

- Lala Lajpat Rai died during a protest in Lahore.

- Result: British government agreed to hold Round Table Conferences to discuss constitutional reforms.

🏛️ 2. Round Table Conferences (1930–1932)

Held in London, aimed to frame a new constitutional structure for India.

| Round | Year | Key Facts |

|---|---|---|

| RTC I | 1930 | Congress boycotted, attended by princely states & minorities |

| RTC II | 1931 | Gandhiji attended after Gandhi-Irwin Pact |

| RTC III | 1932 | Congress again boycotted, limited progress |

- British refused to concede full dominion status.

- No concrete agreement, leading to resumption of the Civil Disobedience Movement.

✊ 3. Civil Disobedience Movement (1930–34)

- Launched by Gandhiji with the Dandi Salt March on 12 March 1930.

- Marked a nationwide non-violent defiance of colonial laws:

- Breaking Salt Law

- Boycott of British goods, taxes, and schools

- Mass resignations and protests

🤝 Gandhi–Irwin Pact (1931):

- British Agreed: Release political prisoners, lift restrictions, allow peaceful protests, Permit use of salt by coastal people.

- Gandhiji Agreed: Suspend movement and attend RTC II.

⚠️ But: Talks in London failed → movement resumed in 1932

🛑 Withdrawn in 1934 due to:

- Harsh British repression

- Internal disunity (e.g., Poona Pact issue)

- Failure of Round Table talks

- Focus shift to constructive work and Harijan upliftment

🧠 UPSC Mains Insight:

“The Simon Commission, Round Table Conferences, and Civil Disobedience Movement represent the cycle of protest, negotiation, and renewed resistance. Together, they highlighted British reluctance to share real power and shaped India’s constitutional path leading to the Government of India Act, 1935.”

🧂 What Was the Salt Law?

The Salt Law was a British colonial law that gave the government a monopoly over the manufacture and sale of salt in India. Indians were forbidden to produce or sell salt independently, and had to buy heavily taxed salt from the British.

⚖️ Key Features:

- Making salt from sea or natural sources was illegal without a government license.

- Even poor Indians living near the sea could not collect salt.

- The salt was taxed — a burden that hit the poorest the hardest.

🧠 Why Did Gandhiji Choose Salt?

- Symbolic: Salt is essential to life, used by all — rich or poor, Hindu or Muslim.

- Universal: Affected every Indian household.

- Simple but powerful: Breaking the Salt Law was non-violent, yet directly challenged British authority.

🏁 Role in Civil Disobedience Movement:

- On 12 March 1930, Gandhiji launched the Dandi March to protest the Salt Law.

- Walked 240 km from Sabarmati to Dandi, making salt from seawater.

- Sparked mass civil disobedience across the country, as thousands broke the law.

🧠 UPSC Mains Insight:

“The Salt Law symbolized the unjust colonial control over basic necessities. By targeting it, Gandhiji turned everyday suffering into political resistance, transforming salt into a weapon of mass civil awakening.”

6. Government of India Act, 1935 – Most Comprehensive Act Before Independence

📌 Background:

- Outcome of Simon Commission, Round Table Conferences, and Civil Disobedience Movement.

📜 Key Features:

🏛️ 1. All-India Federation:

- Attempt to unite British provinces + Princely States (didn’t materialize).

- Provinces declared autonomous.

🗳️ 2. Diarchy abolished in provinces, but introduced at the Centre.

🧑⚖️ 3. Federal Legislature (Bicameral) planned.

🏛️ 4. Provincial Autonomy:

- Indian ministers got real powers in provinces.

- Congress formed ministries in 7 provinces (1937).

🧑⚖️ 5. Federal Court of India established (1937).

🧑🏫 6. Separate electorates extended to minorities, women, SCs, Sikhs, Christians.

🧠 Significance:

- Blueprint of future Indian Constitution (federalism, autonomy, all-India services).

- Most detailed and structured colonial Act.

🛑 However, Indians demanded full Swaraj, not partial autonomy.

🇮🇳 From August Offer to Independence Act (1940–1947): A Complete Story

🧭 1. India & World War II – Did India Join?

- Yes — but without Indian consent.

- On 3rd September 1939, Viceroy Linlithgow unilaterally declared that India was at war with Germany.

- Congress ministries resigned across provinces in protest.

- It marked a breakdown of trust between Congress and the British.

📜 2. August Offer – 8 August 1940

- As WWII intensified, Britain sought Indian support.

- The August Offer proposed:

- Dominion status post-war

- Expanded Viceroy’s Executive Council

- Promise of an Indian Constitution after war

- ❌ Rejected by:

- Congress: Demanded immediate transfer of power

- Muslim League: Felt Pakistan demand was ignored

- ⚡ Gandhi launched Individual Satyagraha (1940–41)

💣 3. Fall of Singapore – February 1942

- Britain suffered a humiliating defeat as Japan captured Singapore — a major British base in Asia.

- It shattered British prestige and raised fears of a Japanese invasion of India.

- British needed full Indian cooperation to defend India.

- This directly led to the Cripps Mission.

🛫 4. Cripps Mission – March 1942

- Headed by Sir Stafford Cripps, sent to secure Indian support in the war.

- Offered:

- Dominion status after the war

- Constituent Assembly to frame Constitution

- Provinces could opt out of the Indian Union (→ seed of partition)

- ❌ Rejected by:

- Congress: Demanded immediate power

- Gandhiji called it a “post-dated cheque on a crashing bank”

- Muslim League: Wanted recognition of Pakistan

- Failure of the mission led directly to the Quit India Movement

✊ 5. Quit India Movement – August 8, 1942

- Launched by Gandhiji with the slogan “Do or Die”

- Demanded immediate British withdrawal

- All major Congress leaders were arrested overnight

- Sparked a spontaneous mass uprising:

- Strikes, boycotts, sabotage of railways and telegraphs

- Brutally suppressed by the British

- However, it showed that British rule no longer had legitimacy

🔥 Role of Subhas Chandra Bose & Azad Hind Fauj (INA)

🧭 Who was Subhas Chandra Bose?

- Former Congress leader and twice elected President of INC (1938, 1939).

- Resigned due to ideological differences with Gandhiji (over non-violence).

- Advocated complete independence through armed struggle.

⚔️ What Did He Do?

- Escaped house arrest in 1941 → travelled to Germany, then Japan.

- Formed the Provisional Government of Free India (Arzi Hukumat-e-Azad Hind) in 1943 in Singapore.

- Became Supreme Commander of the Indian National Army (INA), formed with support from Japan and Indian POWs.

- INA fought alongside Japanese forces in the Burma campaign, tried to invade British India via Imphal-Kohima (1944) — but failed due to logistical issues and weather.

📣 Slogans & Inspiration:

- “Give me blood, and I will give you freedom!”

- “Jai Hind” – INA’s official greeting (now our national slogan)

- Bose named the army units after Gandhi, Nehru, Azad, and Rani Lakshmi Bai.

🧨 Post-War Impact (Most Important for UPSC):

🔥 INA Trials (Red Fort, 1945–46)

- British tried INA officers in public military trials → mass public support for INA heroes

- Massive protests, strikes, and sympathy in the Indian Army, Navy, and Air Force

- Royal Indian Navy Mutiny (1946) was partly inspired by INA legacy

🧠 UPSC Mains Insight:

“Though the INA failed militarily, it succeeded in turning Indian soldiers and civilians emotionally against British rule. Subhas Bose reignited the revolutionary spirit, and the INA trials stirred national outrage. The British realized that even the Indian armed forces no longer stood with them — a key factor in their final decision to leave.”

🌍 6. International Pressure After WWII (1945–46)

🌐 Global Changes:

- WWII ended → Britain was bankrupt and exhausted

- United States opposed colonialism (Atlantic Charter, Roosevelt’s insistence on self-determination)

- Formation of United Nations (1945):

- UN Charter promoted decolonization and self-rule

- Global climate now viewed colonial rule as illegitimate

- Britain was dependent on American loans, which came with political pressure to decolonize

⚓ 7. Royal Indian Navy (RIN) Mutiny – February 1946

- 20,000+ Indian sailors revolted in Bombay and other ports

- Protested racism, poor treatment, and demanded national freedom

- Received public and worker support

- Terrified the British — they realized even the armed forces were turning against them

🛑 8. Britain Accepts the Reality: India Is Ungovernable

- The situation was:

- Economically unsustainable

- Politically unmanageable

- Morally indefensible in global forums

🏛️ 9. Indian Independence Act – 18 July 1947

- Passed by British Parliament

- Based on the Mountbatten Plan (June 3, 1947)

- Came into effect on 15 August 1947

📜 Provisions:

- End of British rule

- Partition into India and Pakistan

- Both dominions would have their own Constituent Assemblies

- Full sovereignty transferred to Indians

🧠 UPSC Mains Conclusion:

“The period between 1940 and 1947 marked the final phase of India’s struggle — where national movements, global shifts, and military unrest converged. The failure of half-hearted constitutional concessions (like the August Offer and Cripps Mission), combined with global anti-colonial sentiment and Britain’s own post-war decline, made India’s independence inevitable.”

7. Indian Independence Act, 1947 – Final Constitutional Step

📌 Context:

- Cripps Mission failed

- Quit India Movement (1942)

- Naval Mutiny (1946)

- Mountbatten Plan accepted → Partition & Independence

📜 Key Provisions:

- Partition of India into two dominions: India & Pakistan.

- End of British sovereignty over Indian laws.

- Constituent Assemblies of India and Pakistan became sovereign.

- Viceroy’s office abolished, replaced by Governor-General (Lord Mountbatten → C. Rajagopalachari).

- British India no longer a colony.

🧠 Constituent Assembly became the supreme law-making body. From here, India began drafting its own Constitution.