📚 BASIC STRUCTURE DOCTRINE

🔍 1. What is the Basic Structure Doctrine?

Basic Structure Doctrine is a judicial innovation developed by the Supreme Court of India, which limits the power of Parliament to amend the Constitution.

👉 In simple words:

Parliament can amend the Constitution—but it cannot destroy its fundamental features.

🟦 ARTICLE 12 – What is “State”?

✅ Simple Explanation:

Article 12 tells us what is meant by “State” when we talk about Fundamental Rights.

It means — whenever any authority from the list below violates your Fundamental Rights, you can go to court.

✅ “State” includes:

| ✅ Included | 🧾 Examples |

|---|---|

| 1. Central Government | Prime Minister’s Office, President, Ministries |

| 2. Parliament of India | Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha |

| 3. State Governments | Chief Minister, State Departments |

| 4. State Legislatures | Legislative Assembly, Council |

| 5. Local Authorities | Nagar Palika, Panchayat, Zila Parishad |

| 6. Other Authorities | Government-controlled bodies like LIC, ONGC, UGC, BCCI (if public in nature) |

⚖️ Why Article 12 is important:

Because Fundamental Rights apply only against the State, not against private individuals (except Article 17, 23, etc.).

🟦 ARTICLE 13 – What is “Law”? & What happens if it violates FRs?

✅ Simple Explanation:

Article 13 protects your Fundamental Rights from any law made by the State that violates them.

🔍 Breakdown of Article 13:

| 🧾 Clause | 🔎 Meaning |

|---|---|

| 13(1) | Any law made before the Constitution (i.e., before 1950) that violates Fundamental Rights is void. |

| 13(2) | The State cannot make any law in future that takes away or reduces your Fundamental Rights. |

| 13(3) | Defines what “law” means: it includes ordinances, orders, rules, regulations, bye-laws, notifications, etc. |

| 13(4) | A constitutional amendment (under Article 368) is not considered “law” under this article. (Added by 24th Amendment after Golaknath case) |

⚔️ Conflict between Article 13 and Article 368

(And how it led to the Basic Structure Doctrine)

🧩 First, recap:

✅ Article 13 says:

Any law violating Fundamental Rights is void.

✅ Article 368 says – Power to Amend the Constitution

Parliament has the power to amend the Constitution. Article 368 gives Parliament the power to amend the Constitution, including any part of it.

❓ So, what’s the conflict?

Let’s break it down simply:

- Fundamental Rights are protected by Article 13.

- Parliament can amend any part of the Constitution through Article 368.

- So the question arose: “Can Parliament amend Fundamental Rights? Or will Article 13 block it?”

⚔️ The Real Question:

Is a constitutional amendment (under Article 368) considered “law” under Article 13?

- If YES, then Article 13 will apply, and Parliament cannot amend Fundamental Rights.

- If NO, then Article 368 will apply, and Parliament can amend anything, even delete rights.

This question led to the biggest constitutional debates in India.

📜 First Constitutional Amendment Act, 1951

👉 Passed on: 18th June 1951

👉 President: Dr. Rajendra Prasad

👉 PM: Jawaharlal Nehru

🧭 CONTEXT: What happened just after the Constitution came into force?

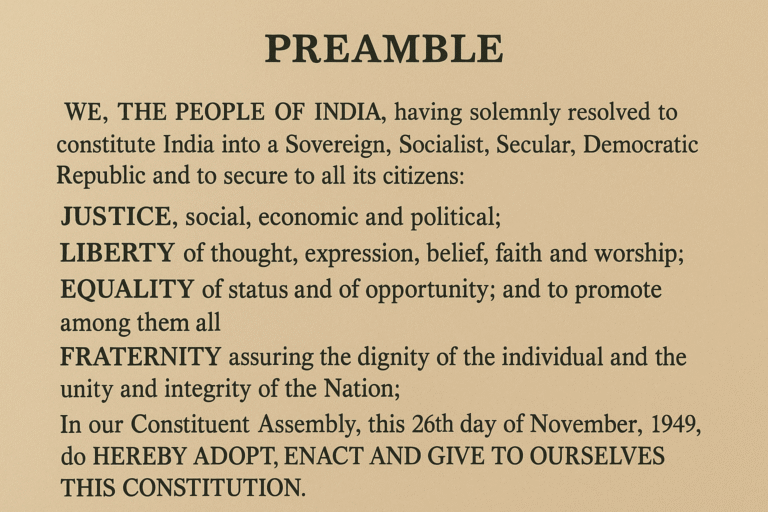

The Constitution came into effect on 26th January 1950.

Within a few months, the Fundamental Rights (especially Article 19 and 31) were being used in courts to strike down major reform laws.

⚖️ KEY PROBLEM: Judiciary vs. Parliament

✅ Fundamental Rights guaranteed:

- Article 19(1)(f) – Right to property

- Article 31 – Protection from property acquisition without compensation

🔥 Real Issue:

🧾 Parliament passed land reform laws to redistribute land to poor farmers (like Zamindari Abolition Acts).

⚖️ But Courts struck them down, saying they violated Right to Property.

Example:

- State of Bihar v. Kameshwar Singh (1951) – Court struck down land reform laws.

🧨 This angered the government. Nehru called it a “Judicial roadblock” to social justice.

🛠️ So, Government brought 1st Constitutional Amendment (1951) to:

🔧 1. Protect land reform laws

→ Added Articles 31A and 31B

→ Protected laws related to land reforms from being challenged under FRs.

🛡️ 2. Added the 9th Schedule

→ Any law put under this schedule was shielded from judicial review.

🗣️ 3. Amended Article 19

→ Allowed the State to impose “reasonable restrictions” on:

- Freedom of speech and expression (to stop misuse)

- Freedom to form associations

- Freedom to practise any profession, etc.

⚖️ What is a Constitutional Bench?

A Constitutional Bench is a bench of the Supreme Court of India constituted to decide important questions of law involving the interpretation of the Constitution.

✅ Legal Basis: Article 145(3)

“The minimum number of Judges who are to sit for the purpose of deciding any case involving a substantial question of law as to the interpretation of this Constitution shall be five.”

So yes:

✅ Minimum number of judges in a Constitutional Bench = 5

🔢 Odd Number Rule – Is It Always Odd?

✅ Yes, in practice, Constitutional Benches always have an odd number of judges.

❓ Why?

Because:

- It avoids a tie in the final judgment.

- A majority opinion must be reached to pronounce the decision.

📘 Major Constitutional Bench Cases: Article 13 vs. 368 & Basic Structure Doctrine

🏛️ 1. Shankari Prasad v. Union of India (1951) – [5-Judge Bench]

🔹 Issue:

Can Parliament amend Fundamental Rights using Article 368, or will Article 13 invalidate such an amendment?

🔹 Background:

- Parliament passed the 1st Constitutional Amendment (1951) to protect land reform laws.

- This amendment added Articles 31A, 31B, and introduced the 9th Schedule.

- It was challenged for violating Right to Property under Article 31 and equality under Article 14.

🔹 Petitioner’s Argument:

An amendment is also a “law” under Article 13(2), and since it violates FRs, it should be void.

🔹 Government’s Argument:

Amendments made under Article 368 are not “law” under Article 13, so Article 13 doesn’t apply.

🔹 Judgment:

- Supreme Court held that Constitutional Amendments are not “law” under Article 13.

- Parliament can amend any part of the Constitution, including Fundamental Rights.

🔹 Impact:

- Gave Parliament full amending power under Article 368.

- Upheld the 1st Amendment and supported land reform.

- Set the tone for future conflicts between Parliament and Judiciary on Constitutional amendments.

🏛️ 2. Sajjan Singh v. State of Rajasthan (1965) – [5-Judge Bench]

🔹 Issue:

Can Parliament amend Fundamental Rights using Article 368, even after judicial review was strengthened post-Shankari Prasad?

🔹 Background:

- In 1964, Parliament passed the 17th Constitutional Amendment Act to further protect land reform laws by adding more acts to the 9th Schedule and amending Article 31A.

- This was again challenged in the Supreme Court for violating Fundamental Rights, particularly Article 14 (equality) and Article 19 (freedom).

🔹 Petitioner’s Argument:

Constitutional amendments that affect Fundamental Rights should be subject to Article 13, and hence void if they violate those rights.

🔹 Government’s Argument:

Reiterated the position from Shankari Prasad — a constitutional amendment is not a “law” under Article 13, and Parliament has full power under Article 368.

🔹 Judgment:

- The Supreme Court upheld the 17th Amendment.

- Reaffirmed that Parliament can amend any part of the Constitution, including Fundamental Rights.

- Amendments are not “law” under Article 13, so Article 13 does not restrict Article 368.

🔹 Impact:

- Reconfirmed Parliament’s power to amend FRs.

- However, Justice Hidayatullah and Justice Mudholkar expressed concern: “Should there be some implied limits on Parliament’s amending power?”

This laid the foundation for the Golaknath case (1967), which would question this logic more deeply.

🏛️ 3. Golaknath v. State of Punjab (1967) – [11-Judge Bench]

🔹 Issue:

Can Parliament amend or take away Fundamental Rights, or are such amendments restricted by Article 13?

🔹 Background:

- The 17th Constitutional Amendment (1964) had added more land reform laws to the 9th Schedule, which were seen as violating Article 14 (equality) and Article 19(1)(f) (right to property).

- The petitioners (the Golaknath family) challenged this amendment, claiming Parliament had no power to alter Fundamental Rights.

🔹 Petitioner’s Argument:

- A Constitutional Amendment = Law under Article 13(2).

- Parliament cannot make any law that abridges or takes away Fundamental Rights.

- Hence, any amendment that violates Fundamental Rights should be declared void.

🔹 Government’s Argument:

- Repeated its earlier stand: Amendments are not “law” under Article 13.

- Parliament has sovereign power to amend the Constitution under Article 368.

🔹 Judgment:

- Supreme Court (6:5 majority) gave a historic ruling:

- Parliament cannot amend Fundamental Rights.

- Constitutional amendments are “law” under Article 13(2) and hence subject to its restriction.

- Fundamental Rights have a “transcendental position” in the Constitution.

🔹 Impact:

- Severely restricted Parliament’s power to make constitutional amendments.

- Created a constitutional crisis — social and land reforms were blocked.

- Led to Parliament enacting the 24th Constitutional Amendment (1971) to restore its amending power.

- Set the stage for the Kesavananda Bharati case (1973).

🏛️ 4. Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973) – [13-Judge Bench]

🔹 Issue:

Does Parliament have the power to amend any part of the Constitution, including Fundamental Rights?

Is there any limit to Parliament’s amending power under Article 368?

🔹 Background:

- After the Golaknath judgment (1967), Parliament’s power to amend Fundamental Rights was blocked.

- To restore it, the 24th Constitutional Amendment (1971) was passed, declaring that constitutional amendments are not law under Article 13 and reaffirming Parliament’s full power to amend.

- Kesavananda Bharati, a seer from Kerala, challenged Kerala’s land reform laws and, more broadly, tested the extent of Parliament’s power under Article 368.

🔹 Petitioner’s Argument:

- Parliament’s power is not unlimited.

- The Constitution is based on certain core principles (like democracy, rule of law) that cannot be altered or destroyed.

🔹 Government’s Argument:

- Parliament has absolute power under Article 368 to amend any provision, including Fundamental Rights.

- There should be no restriction on the amending process as long as the procedure is followed.

🔹 Judgment:

- Delivered by the largest bench in Indian history (13 judges).

- Verdict: 7–6 majority.

Key rulings:

- Parliament can amend any part of the Constitution, including Fundamental Rights.

- BUT it cannot alter or destroy the Basic Structure of the Constitution.

- The Basic Structure Doctrine was formally established for the first time.

🔹 Impact:

- Introduced judicial limits on Parliament’s amending power.

- Basic Structure Doctrine became a permanent feature of Indian Constitutional law.

- Balanced the power between Parliament and Judiciary.

- This judgment is considered the guardian of the Constitution’s soul.

🏛️ 5. Indira Nehru Gandhi v. Raj Narain (1975) – [5-Judge Bench]

🔹 Issue:

Can Parliament bar the judiciary from reviewing the election of the Prime Minister through a constitutional amendment?

🔹 Background:

- In the 1971 Lok Sabha elections, Indira Gandhi defeated Raj Narain in Rae Bareli.

- Raj Narain challenged her election in the Allahabad High Court, which found her guilty of electoral malpractice and invalidated her election.

- While the case was pending appeal, Parliament passed the 39th Constitutional Amendment (1975) which:

- Stated that the election of the Prime Minister, President, Vice President, and Speaker could not be challenged in court.

- Transferred jurisdiction of such matters to a special body to be created by Parliament.

🔹 Petitioner’s Argument (Raj Narain):

- The 39th Amendment violates the Basic Structure by:

- Removing judicial review

- Undermining free and fair elections

- Destroying equality before law

🔹 Government’s Argument:

- The amendment is valid under Article 368.

- Parliament has the power to amend any provision of the Constitution.

🔹 Judgment:

- Supreme Court struck down the 39th Amendment (for the first time applying the Basic Structure Doctrine).

- Held that:

- Free and fair elections are part of the Basic Structure.

- Judicial review is essential for upholding democracy and the rule of law.

- The attempt to protect Indira Gandhi’s election was unconstitutional.

🔹 Impact:

- First case where a constitutional amendment was invalidated for violating the Basic Structure.

- Reinforced the authority of the Supreme Court to check political misuse of constitutional power.

- Strengthened democratic principles and judicial independence.

🏛️ 6. Minerva Mills v. Union of India (1980) – [5-Judge Bench]

🔹 Issue:

Can Parliament have unlimited power to amend the Constitution?

Is the balance between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles part of the Basic Structure?

🔹 Background:

- After the Emergency (1975–77), the Indira Gandhi government passed the 42nd Constitutional Amendment (1976).

- This amendment:

- Gave Parliament unlimited power to amend the Constitution (via changes to Article 368).

- Declared that DPSPs would override Fundamental Rights.

🔹 Petitioner’s Argument (Minerva Mills):

- The 42nd Amendment violates the Basic Structure by:

- Giving Parliament unchecked power.

- Destroying the balance between FRs and DPSPs.

- Taking away judicial review, a core feature of the Constitution.

🔹 Government’s Argument:

- Parliament has full amending power.

- Prioritizing Directive Principles helps achieve socio-economic justice.

🔹 Judgment:

- Supreme Court struck down key parts of the 42nd Amendment.

- Held that:

- Limited amending power of Parliament is part of the Basic Structure.

- The harmony between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles is essential and cannot be disturbed.

- Judicial review cannot be eliminated.

🔹 Impact:

- Reasserted the judiciary’s role as guardian of the Constitution.

- Prevented Parliament from becoming supreme over the Constitution.

- Strengthened the Basic Structure Doctrine by adding:

- Limited amending power

- Judicial review

- Balance between FRs and DPSPs

🏛️ 7. Waman Rao v. Union of India (1981) – [5-Judge Bench]

🔹 Issue:

Do laws placed in the Ninth Schedule of the Constitution after the Kesavananda Bharati judgment (1973) enjoy protection from judicial review, even if they violate Fundamental Rights?

🔹 Background:

- Article 31B and the Ninth Schedule (inserted via 1st Amendment in 1951) protect certain laws from being struck down for violating Fundamental Rights.

- Post-Kesavananda (1973), many more laws were added to the Ninth Schedule to avoid judicial scrutiny.

- Petitioners argued that this blanket protection should not apply to laws that destroy the Basic Structure.

🔹 Petitioner’s Argument:

- Laws placed in the Ninth Schedule after 24 April 1973 (the date of the Kesavananda judgment) must be tested against the Basic Structure Doctrine.

- Parliament cannot use the Ninth Schedule to bypass Fundamental Rights and core constitutional values.

🔹 Government’s Argument:

- Laws in the Ninth Schedule are protected by Article 31B, regardless of when they were added.

- Parliament’s power to place laws in the Ninth Schedule is part of its amending power.

🔹 Judgment:

- The Supreme Court created a clear distinction:

- ✅ Laws added to the Ninth Schedule before 24 April 1973 are safe.

- ❌ Laws added after 24 April 1973 are open to judicial review if they violate the Basic Structure.

- Reaffirmed the Kesavananda Bharati judgment.

🔹 Impact:

- Introduced a cut-off date (24 April 1973) for Ninth Schedule protection.

- Strengthened the Basic Structure Doctrine by preventing its misuse via backdoor entries into the Ninth Schedule.

- Made Parliament accountable even while using its amending powers.

🏛️ 8. S.R. Bommai v. Union of India (1994) – [9-Judge Bench]

🔹 Issue:

Can the President’s Rule (Article 356) be imposed arbitrarily by the Union government?

Are secularism and federalism part of the Basic Structure of the Constitution?

🔹 Background:

- Several state governments were dismissed by the Union using Article 356, claiming breakdown of constitutional machinery.

- Most of these dismissals were politically motivated, not based on actual constitutional crises.

- S.R. Bommai, former CM of Karnataka, challenged the dismissal of his government, triggering a large constitutional debate.

🔹 Petitioner’s Argument:

- The use of Article 356 must be subject to judicial review.

- Secularism and federalism are core features of the Constitution and cannot be violated by political misuse of central power.

🔹 Government’s Argument:

- The President’s satisfaction in invoking Article 356 is final and not justiciable.

- Parliament has the right to decide when there is a constitutional breakdown in a state.

🔹 Judgment:

- Supreme Court gave a historic verdict:

- President’s Rule is subject to judicial review.

- Secularism and federalism are part of the Basic Structure.

- The Union cannot dismiss state governments based on political reasons.

- A floor test in the Assembly is the proper way to determine majority.

🔹 Impact:

- Curbed the misuse of Article 356 by the central government.

- Strengthened India’s federal structure and state autonomy.

- Cemented secularism and federalism as non-negotiable Basic Structure elements.

- Reinforced the idea that constitutional morality overrides political convenience.

🏛️ 9. I.R. Coelho v. State of Tamil Nadu (2007) – [9-Judge Bench]

🔹 Issue:

Can laws placed in the Ninth Schedule of the Constitution after 24 April 1973 be challenged if they violate the Basic Structure Doctrine?

🔹 Background:

- After the Kesavananda Bharati judgment (1973), the Waman Rao case (1981) clarified that laws added to the Ninth Schedule after 24 April 1973 can be reviewed.

- However, there was still confusion over whether Fundamental Rights can be protected from amendments using the Ninth Schedule.

- I.R. Coelho challenged the inclusion of certain Tamil Nadu land ceiling laws in the Ninth Schedule, claiming they violated equality and judicial review.

🔹 Petitioner’s Argument:

- Ninth Schedule cannot be used as a shield to protect unconstitutional laws.

- If a law violates Fundamental Rights forming part of the Basic Structure, it must be struck down, even if in the Ninth Schedule.

🔹 Government’s Argument:

- Laws in the Ninth Schedule enjoy absolute protection under Article 31B.

- Parliament has amending power under Article 368 to place any law in the Ninth Schedule.

🔹 Judgment:

- The Supreme Court gave a landmark ruling:

- ✅ All laws inserted into the Ninth Schedule after 24 April 1973 are open to judicial review.

- ❌ If these laws violate Fundamental Rights that form part of the Basic Structure, they can be struck down.

- Ninth Schedule is not above the Constitution.

🔹 Impact:

- Reinforced the Basic Structure Doctrine as a check on Parliament’s power.

- Made it clear that Article 31B and the Ninth Schedule are not immune from judicial scrutiny.

- Strengthened the role of the judiciary in protecting core constitutional values.

🏛️ 10. Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India (2017) – [9-Judge Bench]

🔹 Issue:

Is the Right to Privacy a Fundamental Right under the Indian Constitution?

Does it form part of Article 21 (Right to Life and Personal Liberty)?

🔹 Background:

- The case arose during challenges to the Aadhaar scheme, where citizens’ biometric and personal data was being collected.

- Earlier judgments like M.P. Sharma (1954) and Kharak Singh (1962) had held that privacy is not a fundamental right.

- The matter was referred to a 9-judge bench to clarify whether privacy is protected under the Constitution.

🔹 Petitioner’s Argument:

- Privacy is intrinsic to human dignity, liberty, and personal autonomy.

- It flows from Articles 14, 19, and 21, and is essential for the right to life.

- Denying privacy would undermine democracy and constitutional morality.

🔹 Government’s Argument:

- Privacy is not an explicitly stated Fundamental Right.

- In a welfare state, the right to privacy can be reasonably restricted for public interest (e.g., Aadhaar).

🔹 Judgment:

- Unanimous verdict by 9 judges:

- Right to Privacy is a Fundamental Right under Article 21.

- It also flows from Articles 14 (equality) and 19 (freedom).

- Earlier rulings (M.P. Sharma, Kharak Singh) were overruled.

- Privacy is essential to human dignity, autonomy, and democracy.

🔹 Impact:

- Marked a historic expansion of Fundamental Rights.

- Strengthened Article 21 and its broad interpretation.

- Though not directly using the Basic Structure Doctrine, it upheld core constitutional values like dignity, liberty, and limited government.

- Became the basis for further challenges to Aadhaar and other surveillance-related laws.